Possibly of interest is a later paper of mine that takes up similar themes: Moten and Arendt: Objects, Antiblackness, and Beginnings.

In this time of crisis, I and many others find comfort in imagining what thinkers we feel close to would say about the COVID-19 pandemic. I have been thinking a lot about Hannah Arendt’s idiosyncratic conception of the world. For her, it is human interaction that creates a world out of the earth; in The Human Condition, Arendt writes that we make a “home for men during their life on earth” by acting together and speaking to each other in a common space. It seems, then, that social distancing is quite literally the end of the world. What Arendt dreads has come to pass: men have become entirely private — that is, deprived of physical interaction with other human beings. What, then, do we do after the end of the world from COVID-19?

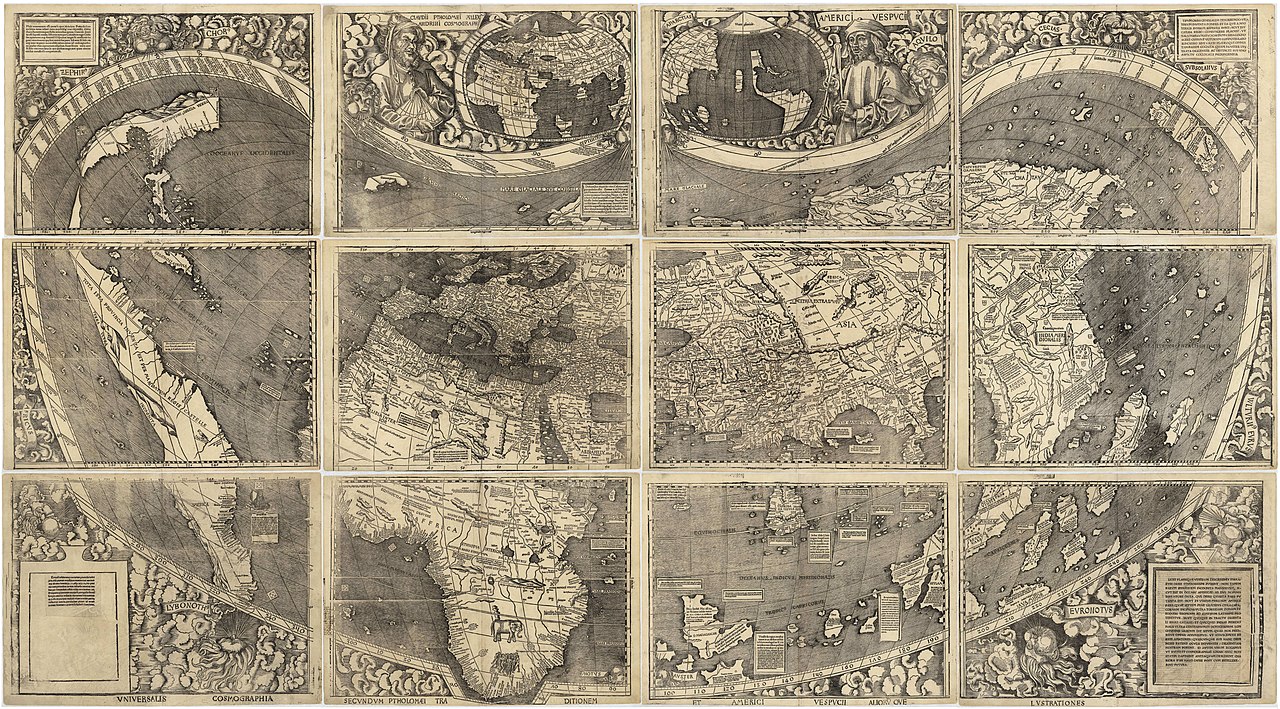

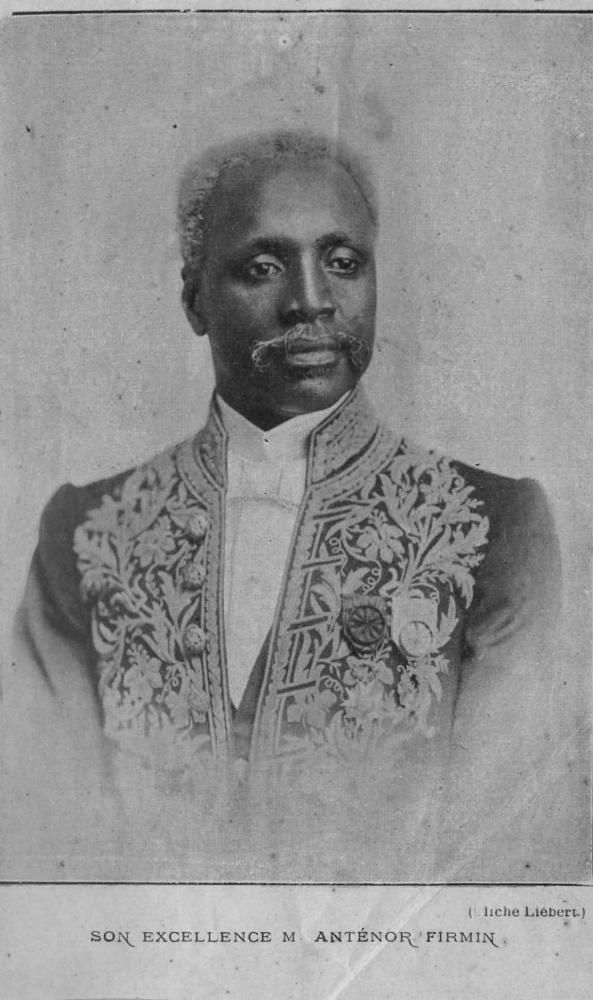

To answer this question, I want to suggest that we look to a bevy of recent works in indigenous and black studies that take seriously the ends of the world that have already happened. The apocalypticism of the climate crisis and of COVID-19 is not novel to people who survived the genocidal onset of modernity. The diseases that devastated indigenous populations in the Americas were many times more deadly than the novel coronavirus; the Middle Passage, too, cut short not just many lives but also spelled the end of entire families, languages, and cultures. In short, the creation and discovery of a new world spelled an end to many old ones. For people who survived these catastrophes and their descendants, the end of the world has long been on their minds.

Recent interventions have brought this rich legacy of thought to bear on the apocalypticism of the climate crisis. We would do well to turn to these recent works as we face another crisis. Just as we can learn much about crisis mobilization from the response to the pandemic, we can begin to imagine a different world post-pandemic by listening to the voices that remind us about the ends of the world that have already happened. In other words, we should think together the end of the world due to colonialism, climate change, and COVID-19. The point of this comparison is not to inspire unfounded hope: to say that the end of the world has happened should never be to diminish its severity. Yet the fact remains that people have always survived and persisted. We should turn to these voices to learn more about the stakes of apocalypticism and what to do after the end of the world.

Continue reading “Black Studies and Geological Thinking”