For Hegel, philosophy requires systematic exposition. It should not be a matter of feeling or intuiting. Nor should philosophy undertake the task of “edification,” a kind of “fog” of “inflamed inspiration.” Rather, philosophy has as its aim material completion that opposes “utterly vacuous naiveté in cognition.” This kind of systematic, complete, ultimate truth is not in substance but in subject, namely the universal individual, the world spirit. Science consists not in an end, but rather in the reflection: the process is of absolute importance.

Continue reading “An Articulation of Hegel’s Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit“Category: Uncategorized

An Articulation of the Prefaces to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason

In his preface to the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant sketches his vision of philosophy’s task after the transcendental turn. For the purposes of this essay, I will limit my discussion to metaphysics, which is also the subject of this first Critique. Kant famously calls metaphysics “the queen of all the sciences” (A viii). He traces a path between the dogmatism (despotic tyranny) and skepticism (complete anarchy) that he says have characterized most previous metaphysics. Kant notes that Locke had attempted but failed to “put an end to all these controversies … through a certain physiology of the human understanding” (A ix). Kant puts this point more strongly still in the preface to the second edition, where he compares the path of metaphysics to other sciences. Logic has “travelled the secure course of a science” since Aristotle (B vii). The path of logic has been relatively easy, though, since it “has to do with nothing further than itself and its own form” (B ix). Metaphysics, by contrast, “has to deal with objects [Objecte] too,” and therefore “logic as a propaedeutic constitutes only the outer courtyard, as it were, to the sciences” (B ix).

Kant’s task is to put metaphysics on the same “secure course of a science” as mathematics and physics. The task of the philosopher is to undertake this kind of scientific inquiry with respect to reason itself. What does this path of metaphysics as science consist in? Well, Kant says, up to now “it has been assumed that all our cognition must conform to the objects.” Since this has “come to nothing,” Kant tells us, “let us once try whether we do not get farther with the problems of metaphysics by assuming that the objects must conform to our cognition” (B xvi). Here he makes an analogy with Copernicus. Before the Copernican Revolution, celestial phenomena were explained as dependent on the motion of heavenly bodies alone, since the Earth was stationary; after Copernicus, these same observed phenomena were explained as dependent on both the motion of heavenly bodies and the motion of the Earth. Kant proposes something analogous: before him, the phenomena of human experience were explained as dependent on the sensible world, with the mind uninvolved in structuring these phenomena; Kant argues, by contrast, that the phenomena of human experience are structured by both sensory data and a basic structure supplied by the human mind. Instead of a sensible world orbiting around a stationary mind, both the mind and objects are involved in structuring the phenomena of human experience. “This experiment,” Kant says, “promises to metaphysics the secure course of a science,” not least because it borrows its structure from the very revolution that also set astronomy on the secure course of a science. Kant is thus “undertaking an entire revolution [in metaphysics] according to the example of the geometers and natural scientists” (B xxii).

Continue reading “An Articulation of the Prefaces to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason“Black Studies and Geological Thinking

Possibly of interest is a later paper of mine that takes up similar themes: Moten and Arendt: Objects, Antiblackness, and Beginnings.

In this time of crisis, I and many others find comfort in imagining what thinkers we feel close to would say about the COVID-19 pandemic. I have been thinking a lot about Hannah Arendt’s idiosyncratic conception of the world. For her, it is human interaction that creates a world out of the earth; in The Human Condition, Arendt writes that we make a “home for men during their life on earth” by acting together and speaking to each other in a common space. It seems, then, that social distancing is quite literally the end of the world. What Arendt dreads has come to pass: men have become entirely private — that is, deprived of physical interaction with other human beings. What, then, do we do after the end of the world from COVID-19?

To answer this question, I want to suggest that we look to a bevy of recent works in indigenous and black studies that take seriously the ends of the world that have already happened. The apocalypticism of the climate crisis and of COVID-19 is not novel to people who survived the genocidal onset of modernity. The diseases that devastated indigenous populations in the Americas were many times more deadly than the novel coronavirus; the Middle Passage, too, cut short not just many lives but also spelled the end of entire families, languages, and cultures. In short, the creation and discovery of a new world spelled an end to many old ones. For people who survived these catastrophes and their descendants, the end of the world has long been on their minds.

Recent interventions have brought this rich legacy of thought to bear on the apocalypticism of the climate crisis. We would do well to turn to these recent works as we face another crisis. Just as we can learn much about crisis mobilization from the response to the pandemic, we can begin to imagine a different world post-pandemic by listening to the voices that remind us about the ends of the world that have already happened. In other words, we should think together the end of the world due to colonialism, climate change, and COVID-19. The point of this comparison is not to inspire unfounded hope: to say that the end of the world has happened should never be to diminish its severity. Yet the fact remains that people have always survived and persisted. We should turn to these voices to learn more about the stakes of apocalypticism and what to do after the end of the world.

Continue reading “Black Studies and Geological Thinking”Forest History of Southern New England

The following analysis uses data published in W. Wyatt Oswald et al., “Subregional Variability in the Response of New England Vegetation to Postglacial Climate Change,” Journal of Biogeography 45, no. 10 (2018): 2375–88, https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13407. The spreadsheet I used is available upon request.

Key points:

- High-resolution data permits reconstruction of Holocene forest cover changes

- Initial forestation after deglaciation in 12 000 BCE led by birch and pine

- Dramatic decline in forest canopy between 1630 and 1708; almost complete recovery by 2001

Berry Pond is an unimaginatively named site north of Boston, Massachusetts (figure 1). Its low elevation (42 m), regular precipitation (1236 mm per year), and soil (mostly glacial till) make it a site typical of southern New England. The authors of this study present an impressively detailed pollen count stretching back to 16 000 years before present (BP), or 14 072 BCE. The sampling gives us data at a very high resolution. This data is freely available through the Neotoma Paleoecology Database. I downloaded this data and here present a brief analysis and interpretation with an eye to tracing the Holocene forest history of New England.

The graph tells a remarkably coherent story of the forest’s response to disturbance (figure 2). The canopy tree count includes species such as maple, chestnut, hickory, oak, and hemlock — characteristic trees of a well-established forest in southern New England. In this category, I also included pioneer trees, namely pine and birch. These trees like open canopy, so they are the first to “pioneer” an area that has no other trees in it. Thus we see that the initial response to deglaciation at 12 000 BCE is a steep climb in the percent of canopy trees, from 56% to 97% in less than 2 000 years. This dramatic increase in forest cover is led by birch and pine, which rise to their all-time high of 75% in 10 800 BCE. Over the next 11 500 years, the relative pollen counts stay pretty similar, with canopy trees at 95–100% and the percent of flowering grasses (indicators of open land) below 5%. In other words, the landscape that native people of New England encountered was mostly forest, without much open land (at least in the area of Berry Pond).

A Neglected Thinker of the Black Atlantic

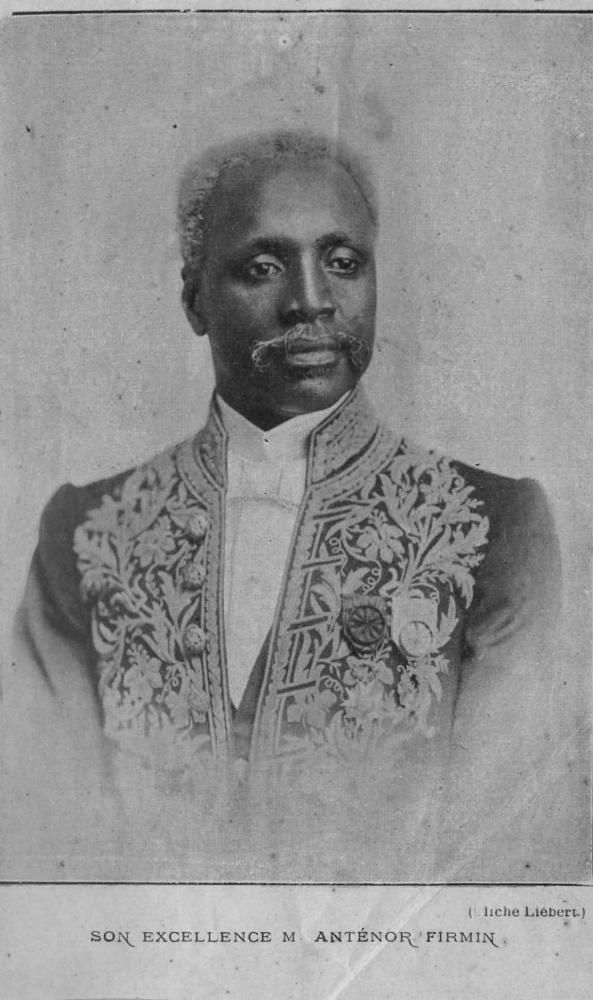

Too few people today know of Anténor Firmin, a Haitian writer, anthropologist, and politician. He is important not just as an early anticolonial figure, but also as a thinker of what he himself termed an anthropologie positive. Firmin wrote his most famous work in 1885, De l’égalité des races humaines, a refutation of the classic 1855 racist tract by Arthur de Gobineau entitled De l’inégalité des races humaines. Firmin’s work is truly remarkable for its rigor and forethought. Scholarship over the past two decades has brought to light many of Firmin’s qualities, not least by issuing new editions of Firmin’s book and its first translation into English. Recent articles have also highlighted his surprising relationship to then-nascent Egyptology; his place in contemporary debates over Darwinism and polygenesis; and his philosophical heritage as traced back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The earliest of these was Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban 2002 article in the American Anthropologist, where she notes that Firmin provides a coherent challenge to race-thinking in anthropology decades before Boas. I want to delve a little deeper into Firmin’s work by highlighting a few passages that I think are particularly exceptional.

Continue reading “A Neglected Thinker of the Black Atlantic”How Do Ice Ages Happen? Exploring Paleosalinity and Thermohaline Circulation

Fill a glass of water from the sea and try to drink it. You gag and your lips pucker. After all, dissolved in that liter of the ocean are around 35 grams of salt. Now, imagine you tried to do this same thing 1 million years ago, 10 million years ago, 100 million years ago, even 500 million years ago. Would you ever be able to drink the water — or would it ever be as salty as the Dead Sea today? These are the questions that investigating paleosalinity helps us answer. We can use a variety of methods — from rough estimates based on our knowledge of the earth system to direct evidence from water droplets preserved in old rocks — to determine how salty the ocean was throughout Earth’s history.

Figuring out how ocean salinity has changed is important not simply because it helps us fill pages in our history book. Changing salinity affects ocean circulation, which in turn has a huge impact on climate. For instance, recent studies have suggested that changes in thermohaline circulation are part of how the Earth cycles between glacial and interglacial periods. In other words, ocean circulation may be the missing link between orbital variations that we know are linked to the cycle of ice ages and the huge swings in CO2 and temperature that are directly responsible for plunging us into glacial periods. In short, tracing paleosalinity helps us understand just how the Earth’s temperature can change so drastically.

This paper is therefore driven by the question: How can paleosalinity help us understand climatic variation, especially that caused by changes in thermohaline circulation? To begin to answer this question, I will present two methods of determining paleosalinity: first, by making an inventory of evaporites; and second, by looking at fluid inclusions. I then turn to the effects that these changes in salinity have on climate, especially by looking at models of how thermohaline circulation would differ and past cases where similar things occurred (for instance, in the Younger Dryas).

Continue reading “How Do Ice Ages Happen? Exploring Paleosalinity and Thermohaline Circulation”The Life of a Hat from Luzon

A version of this object biography was published in the Spring 2019 issue of Contexts: Annual Report of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology.

This hat is a product of — produced by and traded through — colonialism. Its resting place today is the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology in Providence, Rhode Island in the United States of America. There it lies mostly undisturbed; whether dormant or dead is hard to tell. But it was once part of daily life. The hat shielded its owner from the sun and from hazards both natural and man-made. It was also a handy bowl when flipped upside down — quite literally a vessel for life, though even this framing underestimates the hat’s vitality. After all, it has a nose, eyes, and an ear, not to mention some impressive hair. It is more of a head than a hat, in fact. There is something particularly compelling to telling the life story of such an object — from its beginnings in the early twentieth century in Ifugao, a province of Luzon (an island in the Philippines); to its “collection” by an American official in 1912–14; to its acquisition by the Haffenreffer at an auction in 1988.

Say you were to reinvigorate the object. Pick it up (it’s so light!); turn it upside down; feel the contours on the bottom of the bowl; drag your thumb across the tightly woven rattan brim; note how the light glistens off what seems like its polished metal exterior. When you’re done with the physiognomy, try moving your head closer and breathing in. The smell of the wood can’t help but evoke memories, fantasies, even disturbing thoughts. After all, its military past is ingrained in the pores of the wood and the basketry of its brim. What has the hat seen? What has it heard, touched, smelled?

Continue reading “The Life of a Hat from Luzon”How Salty Has The Sea Been Over the Past 541 Million Years?

Take a bottle of water from the sea and try to drink it. You gag and your lips pucker. After all, dissolved in that liter of the ocean are around 35 grams of salts (mostly sodium chloride). Now, imagine you tried to do this same thing 1 million years ago, 10 million years ago, 100 million years ago, even 500 million years ago (that is, throughout the Phanerozoic eon). Would you ever be able to drink the water? Alternatively, would the sea ever have been so salty that today’s ocean creatures would not have survived? A 2006 article by Hay et al. helps answer precisely these questions. The authors tracked variable chloride levels to demonstrate how salinity has changed throughout the Phanerozoic, noting a significant overall decline. These changes have had important effects on ocean circulation and on plankton levels — and possibly contributed to the explosion of complex life in the Cambrian, 541–520 million years ago. Continue reading “How Salty Has The Sea Been Over the Past 541 Million Years?”

My Independent Concentration

I recently found out that my proposal for an independent concentration in Critical Thought and Global Social Inquiry has been approved! Just what does this mean, and why am I so happy about it?

First of all, a few words on what an independent concentration is (at Brown). Apart from the standard concentrations (majors) we offer, every student has the opportunity to design their own course of study. This concentration proposal must be reviewed and approved by a subcommittee of the College Curriculum Council, the same body that approves regular concentrations. The process of proposing an IC is supervised by the Curricular Resource Center, which has multiple peer student staffers who meet regularly with students who want to create an IC. The actual proposal is long and rigorous. Furthermore, the committee almost as a rule rejects first-time applications; there is a heavy emphasis on the process of proposing an IC as a conversation between the committee and the student with the aim being to create a well-articulated, coherent, and rigorous course of study that aligns with Brown’s wider educational goals. I personally found this process extremely rewarding: it helped me process my interests and a few thoughts that had been rolling around in my head (many because of courses I had taken). I am now much more articulate about these interests and I have a much better idea of how they align with my broader life goals. Although the process of creating an IC is arduous, for me it was well worth it.

To explain what my Independent Concentration is about, here’s an excerpt from my proposal (which you can find in full here):

What is Critical Thought and Global Social Inquiry? It is the study of global social phenomena such as postcolonialism, nationalism, and global justice through the philosophical lens of critical theory. I think dialectically about both the institutions derived from the Enlightenment and the practices, communities, and identities developed and deployed in resistance to these institutions. I am thus equally invested in studying the universal and metropolitan on the one hand and the particular and peripheral on the other. As a field of study, I imagine my Independent Concentration as a conversation with a number of figures invested in this dialectic – chief among them Edward Said, Hannah Arendt, and Cornel West. In many ways, this field of study is constituted by its intellectual genealogy: while investigating questions about how societies cohere, how politics functions, and how the past shapes our present (and drawing on sources from many times and places), what distinguishes Critical Thought and Global Social Inquiry is its distinctive perspective. This reflexive, provisional approach is gathered from the theoretical consciousness developed through the philosophical tradition of critique. Given my commitment to provisionality and reflexivity, I do not intend through this concentration to provide conclusive answers to the questions I described above. The fundamental aim of Critical Thought and Global Social Inquiry is instead to develop concrete questions, modes of interpretation, and resources for action that resonate across different commitments and backgrounds. Through my concentration, I develop a map – a way to navigate the incredible diversity of thought and experience our world has to offer.

Working with Women’s Refugee Care

In Fall 2017, I was fortunate enough to take an engaged course in the French department called L’expérience des réfugiés et immigrés (The Experience of Refugees and Immigrants). This course was developed last summer and offered for the first time this year (see article for more). It combined a survey of Francophone texts by and about migration with an engaged component: working with Women’s Refugee Care (WRC). My French improved because I got the chance to use it in a setting with no safety net: in the community engagement portion of the course, French really was the best means of communication. More importantly, this course was a great opportunity to get involved with a local nonprofit and explore the idea of engaged scholarship (which I’m continuing to do through the Engaged Scholars Program in Archaeology).

My work with Women’s Refugee Care centered on three interviews I did with members of the Congolese refugee community here in Providence. Along with Jeanelle Wheeler, my wonderful colleague, we got to know the community, attending a few gatherings and meeting lots of interesting people. We then arranged interviews with a few of those we met at their homes. After recording the interviews, we translated them into English and then posted them on the WRC blog.

I’m particularly happy with the final result: interviews with Katerina, Aline, and Sylvie. I encourage you to read what they have to say — not just to admire their successes and appreciate the challenges they faced, but to acknowledge them as multifaceted human beings. I also wrote an introduction to the interviews (in French), where I reflect on the entire experience, including obstacles, challenges, and the path we took in presenting them as we did. If you find this interesting or stimulating, I would love to know — just add a comment here or send me an email.1